Obstruction Of Governmental Administration Cases

Westchester Criminal Defense Lawyers Who Handle Obstruction Of Governmental

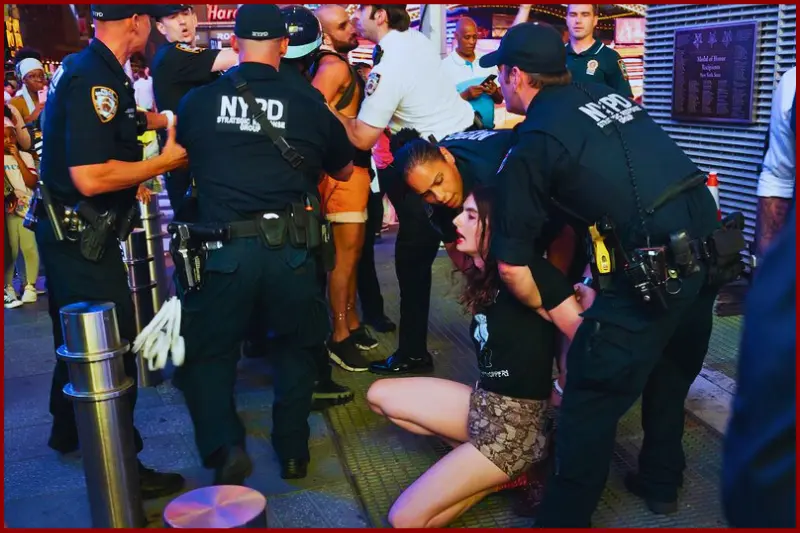

Obstruction of Governmental Administration is often overly charged by the police in both New York City and Westchester, most of whom don’t really understand what it means. Our White Plains criminal defense lawyers have seen many cases of obstruction of governmental administration improperly charged by police officers in Yonkers, White Plains, Mount Vernon, New Rochelle, Port Chester, Mamaroneck and other areas. All too often the police think that they can arrest and charge someone with obstruction of governmental administration just because they don’t cooperate with the police. Police officer often threaten a baseless charge of obstruction of governmental administration to get a witness or defendant to give them information. Our Westchester County criminal defense lawyers are committed to fighting these baseless charges and even bringing false arrest and malicious prosecution charges against police officers that abuse their authority by bringing these baseless charges.

Under New York Penal Law § 195.05 a person is guilty of obstructing governmental administration when he intentionally obstructs, impairs or perverts the administration of law or other governmental function or prevents or attempts to prevent a public servant from performing an official function, by means of intimidation, physical force or interference, or by means of any independently unlawful. An essential element of this offense is that the governmental function that citizen allegedly interfered with, have been authorized and that there be a physical act which is interferes with the lawful government function. If either of these are missing, there is no obstruction of governmental administration.

So the initial question often arises, what is an authorized acts in terms of the obstruction of governmental administration law. While the police are authorized to investigate an incident and to question witnesses or suspects about it, the police do not have the authority to force a defendant to remain in a location to answer questions. The power of law enforcement to detain citizens involuntarily is subject to Constitutional limits set by the Fourth Amendment and jurisprudence has set forth a hierarchy of police authority to stop and detain criminal suspects, based on levels of suspicion. The first and least intrusive form of police action is a request for information, which is permissible as long as the police have some objective reason for the intrusion and are not acting on a whim or hunch. The second level is the common law right to inquire, under which a police officer with a founded suspicion that criminal activity is afoot may interfere with a citizen to the extent necessary to gain explanatory information, but short of a forcible seizure. Next, New York Criminal Procedure Law § 140.50 gives the police the authority to stop a suspect and demand the suspect’s name, address and an explanation of the suspect’s conduct when the police officer reasonably suspects that the suspect is committing, has committed or is about to commit a felony or a misdemeanor. However, this does not apply to violation level offenses such as disorderly conduct, unlawful possession of marijuana or harassment

It is well settled that when the police lack a reasonable suspicion that a particular person has committed, is committing or is about to commit a felony or misdemeanor, which is necessary to justify a forcible stop, they cannot stop an individual who exercises his or her right to be let alone and to refuse to respond to police inquiry. An individual to whom a police officer addresses a question has a constitutional right not to respond and he may remain silent or walk or run away and his refusal to answer is not a crime. Though the police officer may endeavor to complete the interrogation, absent probable cause to believe that the individual has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime, he may not pursue or seize the individual, even though he ran away.

Often the police allege that a particular individual committed obstruction of governmental administration by not cooperating in their investigation, however, the caselaw in New York is clear that a private citizen has no obligation to cooperate and his or her failure or even a refusal to cooperate cannot establish obstruction of governmental administration. The New York Courts have recognized that a citizen’s act of leaving, or even running from, the police and attempting to leave the scene does not violate the obstruction of governmental administration statute. Were the law otherwise, it would follow that whenever any barrier is placed in the path of process and/or arrest, this class A misdemeanor (obstructing) could be added. The New York Courts have held that even running from a police officer is not a crime, although such activity may create rights and duties for police, such as to proceed to obtain a warrant or assuming probable cause to arrest without a warrant, chase and apprehend the defendant, it is not conduct that constitutes the crime of obstructing governmental administration.

Or Call (212) 858-0503

Law Office of Michael H. Joseph, PLLC

The Law Office of Michael H. Joseph, PLLC, has been helping injured victims recover compensation for their injuries for over 25 years. Our attorneys are members of several prestigious organizations, including:

- New York State Trial Lawyers Association

- American Association for Justice

- New York County Bar Association

- Westchester County Bar Association

To request your free initial consultation with our team, call our New York City office at (212) 858-0503 or our White Plains office at (914) 574-8330. You can also request a case review online.